Published: 15th January, 2019

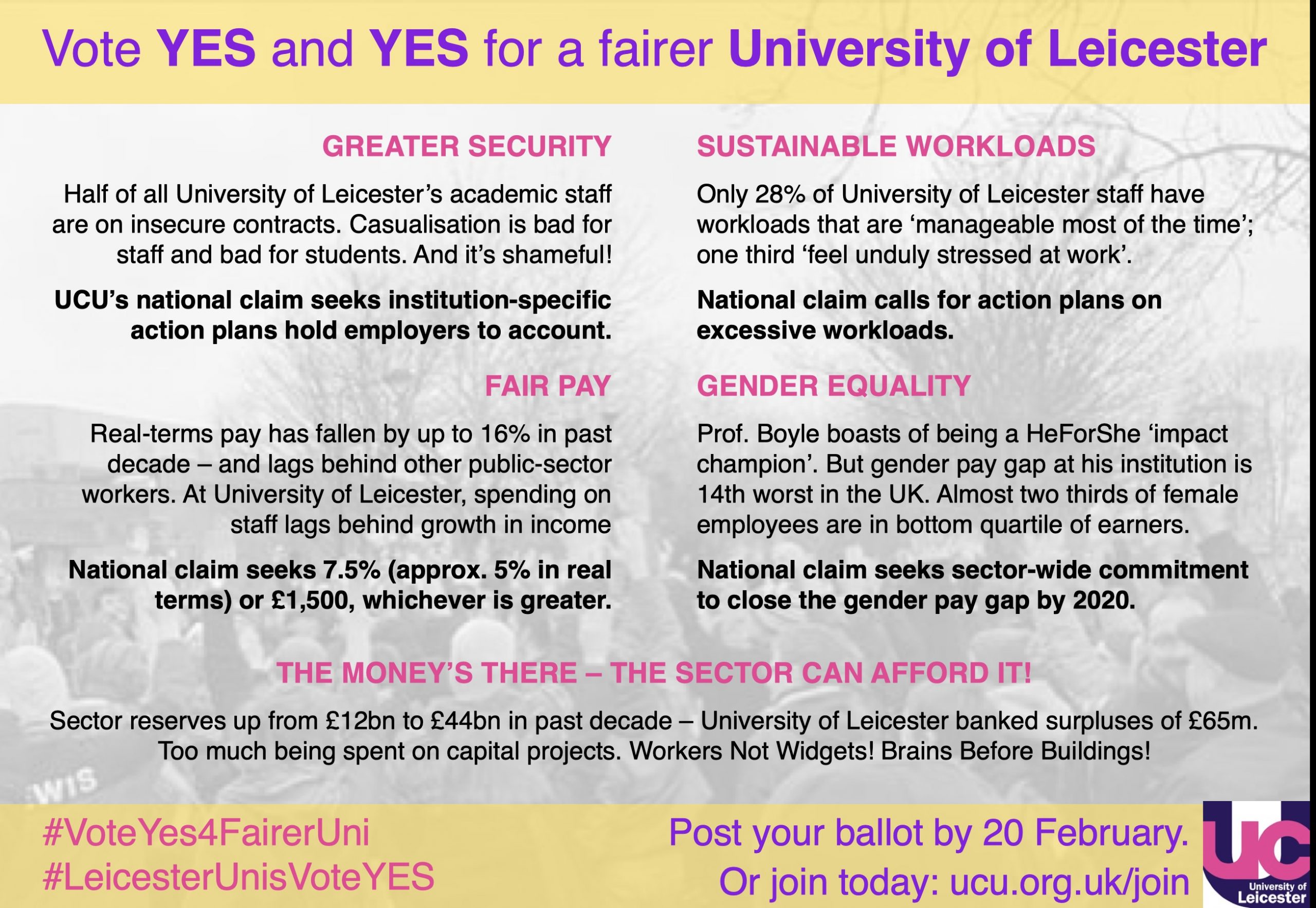

Voting is now open to decide whether UCU members will take strike action (and action short of strike) in support of our claim (vis-a-vis our employers) regarding pay, equality, workloads and precarious contracts.

The ballot closes on 22 February – so you must send off your ballot paper by 20 February to make sure your vote is counted. In line with recent legislation (the 2016 Trade Union Act), at least 50% of UCU members must cast a vote for any resulting industrial action to be legal. You should receive your ballot paper by Friday 18 January at the latest – please check which address UCU has for.

Let’s take a look at the four elements of the claim, examining the national picture and the situation at University of Leicester. The 2017/18 Financial Statements have just been published, so we draw on those where possible. We’ve also drawn on a briefing we published in October last year, ‘Pop goes the weasel’. We conclude by explaining why the higher education sector in general and University of Leicester in particular can afford to accept our claims.

Real wages for a typical UCU member – from a starting lecturer up every other point on our pay spine – have declined by between 5 and 11 per cent over the past two decades (depending on whether inflation is measured by the Retail Price Index or the Consumer Price Index). In just last 10 years, our real wages have fallen by something between 9 per cent and 16 per cent. (That’s a worse deterioration than other workers in the UK’s economy: real median wages in Britain are 2–13 per cent lower than they were in 1998.)

At University of Leicester, spending on staff costs has risen – by about 50 per cent in the past 20 years – but it hasn’t risen nearly as much as the institution’s income and total expenditure, which have both grown by 70 per cent over the same period. In just the past year (i.e. between 2016/17 and 2017/18), our employer’s income grew by 8.2 per cent; spending on staff by just 3.3 per cent. The University Leadership Team claims that spending less on staff as proportion of overall spending – ‘moving us closer to the sector average’ – is a good thing. Leicester UCU strongly believe that a university is made by its employees (lecturers and researchers, but also librarians, IT specialists, cleaners, counsellors, time-tablers, porters, cooks, gardeners…). Not only would we like to work in a university that spends more on us – but that’s the sort of university we would like our children to attend!

No surprise then that we agree with UCU’s pay-claim principle of ‘keep up and catch up’ and think completely reasonable the specific demand of an increase of 7.5 per cent (about 5% per cent once you take inflation into account) or £1500 whichever is the greater.

Not all University of Leicester employees have suffering falling pay. Our president and vice-chancellor seems to be doing OK. In 2017/18 his total emoluments totalled £313,000, including £6,000 USS pension contribution, accommodation benefits worth £12,000* and – incredibly, given the way the institution he leads has performed in the precious rankings – a bonus of £10,000. All in all, Professor Boyle received £23,000 more in 2017/18 than he did in 2016/17. That’s a rise of 8 per cent – and we thought he’d agreed to ‘pay restraint’! By way of comparison, the University of Leicester is currently advertising for an Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Assistant, to work in the department of human resources – ‘You will be joining a dynamic team whose role is to lead the growth and development of equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) across the University’. The salary: £19,202 to £22,017 per annum.

But Professor Boyle is just the most egregious symbol of inequality at the University of Leicester. The institution continues to claim that it is ‘leading by example on equalities, diversities and wellbeing’ :

We remain committed to our ambitions in relation to Athena SWAN accreditation, the Stonewall Index and other charters of equality and we are proud of our role as one of only 10 universities in the world taking the lead for the UN’s HeForShe movement.

Yet, there seems to have been no progress on gender equality. It’s true the median gender pay gap has closed slightly, from 25.5 per cent in 2016/17 to 22.7 per cent in 2017/18 – we interpret this as meaning the ‘typical’ woman earns 22.7% less than the ‘typical’ man. But the mean gender pay gap has widened, from 23.1 per cent to 24.1 per cent. This is 14th worst in the UK, according this report in Times Higher. Moreover – and another terrible signal from a HeForShe ‘champion’ – while 7.6 per cent of male employees received a bonus in 2017/18, only 4.8 per cent of female employees did. And – from the Times Higher report again – almost two-thirds of University of Leicester’s female employees are in the bottom quartile of earners.

Our employer did respond to its gender pay gap, acknowledging in March that ‘there is progress to be made’. Leicester UCU’s first response to this report was ‘one of dejection, but certainly not of surprise’: it described the report as ‘narrow,unradical, wholly inadequate’. It’s possible the new Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Assistant will make all the difference. But – just in case – we think UCU’s demand that for employers UK-wide to commit to closing the gender pay gap by 2020 is worth supporting.

According to UCU, 46 per cent of universities use zero-hour contracts. This is obviously bad for those workers those themselves – for all sorts of reasons – and we believe it is wrong ethically. But, even if we were to disregard those costs, casualisation is bad for education: bad for students and also for other staff. In a nutshell lecturers’ working conditions are students’ learning conditions: students will not receive the best education if their teachers are worried about making next month’s rent or mortgage payment and are juggling two or three ‘gigs’.

University of Leicester’s record here is worse than the national average. According to data collected by UCU (available here), in 2016/17 half of all academic staff were on insecure contracts (either fixed-term or ‘atypical’). (In fact, one trigger for our successful summer campaign was what we described at our employer’s ‘shameful treatment of fixed-term contract staff’.)

UCU’s national claim seeks institution-specific action plans hold employers to account. We’re right behind this!

We work too much. Certainly we work more than we are paid for. In 2016, a UCU survey found that HE staff in the UK were working more than 50 hours each week on average, with 83% reporting that ‘the pace or intensity of work [had] increased over the past three years’. Two thirds of staff said ‘their workload is unmanageable at least half of the time’; 29 per cent reported that their workloads ‘were unmanageable all or most of the time’.

Results for University of Leicester are in line with these worrying national findings. In the UCU survey 80 per cent of us reported an increase in pace and intensity of work; more than half of us reported a significant increase. Only 28 per cent said their workloads were ‘manageable most of the time’; more than a quarter reported workloads that were ‘unmanageable most of the time’ and a worrying 4 per cent said their workloads were ‘entirely unmanageable’. Our employer’s own staff survey of 2017 drew similar findings to the UCU survey. For example, almost one third of us agreed that we ‘feel unduly stressed at work’ and a similar proportion complained about ‘work-life balance’.

Given this, UCU’s call for action on excessive workloads seems right on message!

Vice-chancellors and other university ‘leaders’ like to pontificate on the various challenges facing higher education – threats post-Brexit, the possibility that maximum fees for some courses could be cut to £6,500, for instance – usually as a prelude to making ‘difficult decisions’. But according to Higher Education Statistics Agency figures, UK universities banked surpluses (the terms ‘exempt charities’ like universities use for what is, essentially, profit) totalling £2.3 billion between 2015/16 and 2016/17. Since 2009/10 universities’ overall reserves have expanded from £12.33 billion to £44.27 billion – even taking inflation into account, they have tripled! As the proportion of total expenditure allocated to staff has fallen – by 3.35 per cent over the past seven years – the percentage devoted to capital spending has shot up – by 34.9 per cent over the same period.

According to its financial statements, in the past decade (since 2008/09) University of Leicester has accumulated surpluses totalling £64.8 million. In the year 2016/17–2017/18, financial performance was below the 10-year average, but the institution still made a surplus of £3.6 million – sufficient to grant every single employee £950.

Of course, we don’t get the complete picture if we look only income, expenditure and surplus in the aggregate. We also have to see where the money is going – this is what we did in ‘Pop goes the weasel’. As we know very well, the University Leadership Team led by Professors Boyle and Burke has an ‘ambitious capital programme’. Following accounting convention, capital expenditure in the present leaves a ghostly – yet very material – trail in the future: it appears as depreciation in the income and expenditure accounts. (This happens because a new building is assumed to depreciate over 50 years. Spend £10 million today and £200,000 appears as expenditure – under ‘depreciation’ – for the next 50 years.) Given Professor Boyle’s capital ambitions, expenditure on ‘depreciation’ is rising – from £16 million in 2016/17 to £19.3 million in 2017/18 – a 20 per cent increase. Remember that spending on staff grew by only 3.3 per cent.

In short, the money is there – in the higher education sector, in general, and at the University of Leicester. The University leadership seem to have a vision of shiny new buildings and laboratories, elegant plazas and whizzy things that go bang. But they are not prepared to invest in the human beings who do the teaching, carry out the experiments and write the research papers – along with all those professional services and ancillary staff who support them and their students. The university as trompe-l’œil.

Our perspective is different. Our message is workers not widgets – brains before buildings.

To reiterate. The University and College Union is now asking its members to decide whether we are prepared to take strike action to support our claim regarding these four issues: our pay, gender equality, secure contracts and sustainable workloads. It is a postal ballot which closes on 22 February – so you must send off your ballot paper by 20 February at the latest. (Check the address UCU has for you if haven’t received a ballot by Friday 18 January.)

The committee of Leicester UCU recommends that you vote YES to strike action and YES to action short of a strike.

If you want to get involved in branch activity we’d be delighted to welcome you – please get in touch!

* We’re a little puzzled at the University accountants’ valuation of the vice-chancellor’s accommodation. This property site, for instance, suggest a rent of £1000 per month will get you a three-bedroom house. Professor Boyle gets Knighton Hall!

Addendum (22.2.2019): In response to this we received the following from Martyn Riddleston, the finance director: The University purchased Knighton Hall in 1947 and it has been our residence used for the Vice-Chancellor since that time. The first Vice-Chancellor to live in Knighton Hall was Frederick Attenborough. The Hall is also used extensively for University events hosted by the Vice-Chancellor. In the 2017/18 year he hosted 30 events at the Hall, all of which took place in evenings or at weekends. Throughout the year a number of visitors and guests were accommodated overnight in the Hall. The value disclosed in the Financial Statements in respect of the Hall represents the taxable benefit of the Vice-Chancellor’s private space in the Hall, using a method which has been approved by HMRC. The majority of the space within the Hall is set-aside for hosting University events.